The last 20 years have been called the decades of disruption for good reason. Over this period, new technologies and products have been introduced, have peaked and have become obsolete at a rate never seen before.

Recognizing how quickly a disruptive technology can impact current state-of-the-art products can be useful in anticipating change and developing an appropriate response to market demands for constantly upgrading performance, both at the system and component level.

This article is to review some of the major advances that have been made in the electronics industry over the past 20 years.

|

2000

|

2010

|

2020

|

| USB 1.0 @ 1.5Mb/s |

USB 3.0 @ 5Gb/s |

USB 4 @ up to 40Gb/s |

| Blackberry |

iPhone |

Smartphones as an interface device |

| 3G cellular |

4G cellular |

5G cellular |

| 3.125Gb/s NRZ |

25Gb/s NRZ |

112Gb/s PAM4 |

| Rise of data centers |

Cloud computing |

Edge / Fog computing |

| Copper circuits |

Increasing fiber options |

Silicon photonics / expanded beam technology |

| Many proprietary connectors |

Licensed second-sourced connectors |

Rise of open component / system standards |

| PCIe 1.0 @ 2.5GT/s |

PCIe 3.0 @ 8GT/s |

PCIe 5.0 @ 32 GT/s |

| 10Gb Ethernet |

40/100Gb Ethernet |

200/400Gb Ethernet |

| Multilayer enhanced FR4 backplanes |

Multilayer high- performance laminate backplanes |

Orthogonal midplane, cable backplanes twinax cabling |

| Chip feature size 90nm |

Chip feature size 32nm |

Chip feature size 5-10nm |

| Antenna TV |

Cable TV |

Streaming TV |

Universal Serial Bus Connectors

The performance of any computing device can be severely hobbled by limiting its capacity to accept and deliver data to the outside world. A data bottleneck at the input/output (I/O) panel will throttle information throughput to the capacity of the least efficient portal.

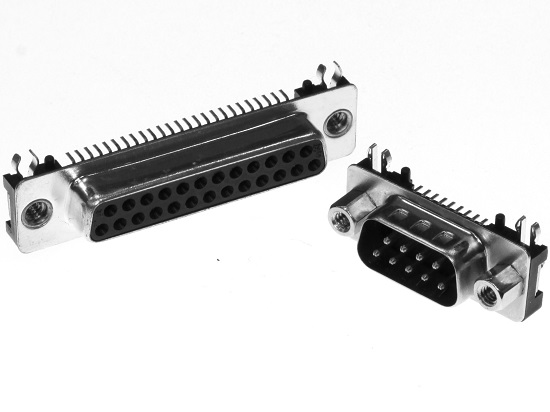

For many years, variations of 15- and 25-pin subminiature D shell connectors were capable of providing adequate I/O data rates to peripheral devices. With its origins in the world of military applications, reliable pin and socket contacts, and rugged shells, these connectors were modified to commercial versions at consumer prices and became a de facto standard, appearing in everything from video connections to mouse and keyboard interface applications.

As demands for data rates increased from kilobits to megabits, and the space available for external interconnect decreased, new connector interfaces were required. In 1996, a consortium of electronic industry leaders formed the USB Implementors Forum and released the first iteration of the Universal Serial Bus interface.

The refined USB 1.1 specification was published with the objective of replacing a confusing array of existing interfaces that threatened compatibility among an expanding array of peripheral devices, including flash memory and external hard drives, scanners and printers. Initial transfer rates were 1.5Mb/s through a relatively small rectangular connector using low insertion force leaf contacts that could support thousands of mating cycles. The user-friendly metal housing and post molded backshell could be mated only in one direction, assuring proper polarity.

A major advantage of the USB standard is the ability to deliver power as well as signal, enabling remote devices to operate without an external power source. Signal contacts were recessed to allow power contacts to mate first. This “hot mating” capability is another key feature of the USB interface.

The USB standard A and B configurations quickly achieved namesake status and were widely adopted throughout the industry.

Faster, More Versatile Connections

The USB interface is a perfect example of a standard that continued to evolve to meet the performance and packaging requirements of the industry it serves.

The USB 2.0 standard, released in 2000, was rated up to 480Mb/s. In addition to retaining the same A and B form factors, two miniaturized versions were introduced. USB Mini-A and B improved the signal density of the interface to address the burgeoning market of portable devices, including laptop computers and tablets, where I/O space is at a premium. Micro A and B connectors consumed even less space on devices. The added advantage of distributing power along with data opened up entirely new classes of equipment. These miniaturized connectors quickly become a standard in charging applications.

In 2011, the upgrade to USB 3.0 introduced several new interface configurations and further pushed transfer rates to a maximum 4.8Gb/s. A 9-pin connector referred to as “Superspeed USB” features two rows of contacts to allow use of the standard A shell profile as well as backward electrical compatibility. A new type B introduced a new profile, while a Micro B configuration known as the “sidecar” interface become standard in external memory hard drive applications.

USB 3.1 Gen 2 offers transfer rates to 10Gb/s, and introduced some confusion when the Implementors Forum announced USB 3.2 running at 20Gb/s.

The Current Standard

USB Type-C is the most current and speedy interface in the family and finally solved the problem that prior versions required connectors mate in only one direction. USB-C utilizes a rugged symmetrical 24 pin interface that is reversible. Not only is it 60% smaller than Type A, but it now features 10Gb/s transfer rates with the capability of distributing up to 100 watts of power. A somewhat confusing extension dubbed USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 is rated to 20Gb/s.

Never satisfied with current achievements, the USB Implementors Forum published the USB 4 specification in September of 2019. The connector will remain Type C but will integrate Intel Thunderbolt 3 technology with transfer rates to 40Gb/s. USB 4 is backward compatible with USB Type-C protocols, including USB 3.2, DisplayPort, and Thunderbolt 3, simplifying connectivity for entirely new generations of equipment. Devices sporting this new interface are expected by 2021.

A standard that is static has little chance of remaining relevant in an industry that is experiencing continuous change. The USB Implementers Forum has demonstrated its commitment to constant upgrades, enabling USB to continue to play a key role in the design of next-generation equipment.

Source of the article: https://reurl.cc/GV4WVd